Discovering Escapability

Scientific Illiteracy

Experiences of Internships

Weightlifting Coaches Should Have Been Weightlifters

Programming Planning

Is It Time For Real Coaching Certification?

Exercise Order and Selection

Is One on One Coaching (Personal Training) the Best Mode?

We Are All Fighting the Clock!

Thoughts on 100% and Intensity Zones

Platform Coaching Demeanor

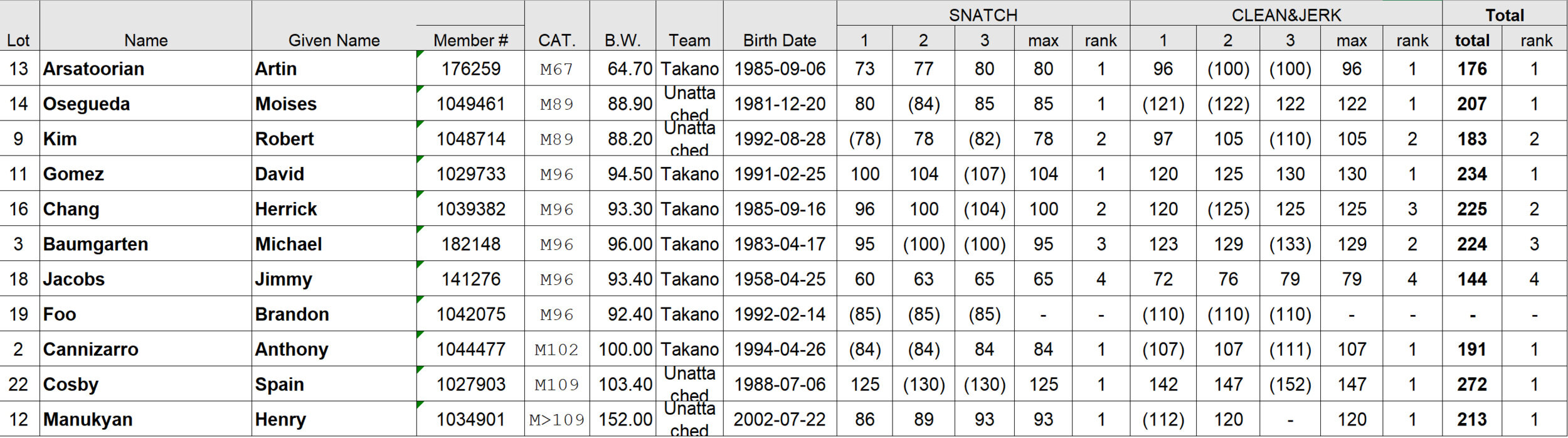

Results of the Charles Darwin's Birthday Weightlifting Championships

The Men’s Results

The Women’s Results

The Role of the Arms in the Snatch

Coaching Perspectives: Science and Voodoo Weightlifting

Your Clean & Jerk vs Your Bodyweight and a Technique Coaching Philosophy

Weightlifting Footwork--Why and When

From observing lifters at local competitions and some national as well, I’ve come to the conclusion that the issue of footwork is not well understood. Footwork can make a difference in completion percentage and so it is a topic that needs to be addressed by both lifters and coaches. I’m writing about the footwork involved in the performance of the snatch, clean and power jerk. The split jerk footwork is another completely different beast.

What is footwork?

Footwork represents a major part of the athleticism of a sport movement. As bidpedals, footwork is an indicator of how well we are using our legs to perform athletic tasks. During the snatch, power snatch, clean, power clean, power jerk and squat jerk, footwork can make a significant difference in the percentage of successful lifts.

Pulling stance

Most athletes pull best when their feet are placed at hip width. This insures that the force vectors are directed vertically.

Squatting or receiving stance

This stance is generally wider than pulling stance. For most athletes a receiving stance that is too narrow will force the torso to lean forward excessively which could result in a loss of the weight forward.

Foot work that minimizes air time

Ideally the athlete should move the feet from pulling stance to squatting stance while dropping under the weight. This should be done with the least amount of air time possible so skimming of the feet is advised. While the feet are in the air the lifter cannot generate any force against the bar, so it is best to re-contact the floor as quickly as possible.

Why move the feet?

Some athletes don’t move the feet, but for most people it is advisable to do so for two reasons.

1. Moving the feet out to the proper receiving stance provides more stability and a greater chance to complete the lift.

2. Moving the feet “unlocks” the complete extension of the hips and allows for a quicker hip flexion when dropping under the bar.

When to move the feet

To begin with the pull should involve the full plantar flexion of the ankles, full extension of the knees and hips. While some coaches have questioned the necessity for full plantar flexion in relationship to bar height, the fact is that full hip extension is not possible without full plantar flexion.

FOOT MOVEMENT SHOULD BEGIN WHEN THE ATHLETE STARTS TO DROP UNDER THE BAR!

Once the aforementioned hip and knee extension and plantar flexion take place, the foot work should commence immediately along with the drop under the bar. Moving the feet prematurely will negate the full extension of the hips and knees in the pull (or jerk drive as the case may be).

Athletes can work on their footwork by practicing the drill in the accompanying video.

The Case for Technique Competitions

Use Sequence Photos to Develop the Coaching Eye

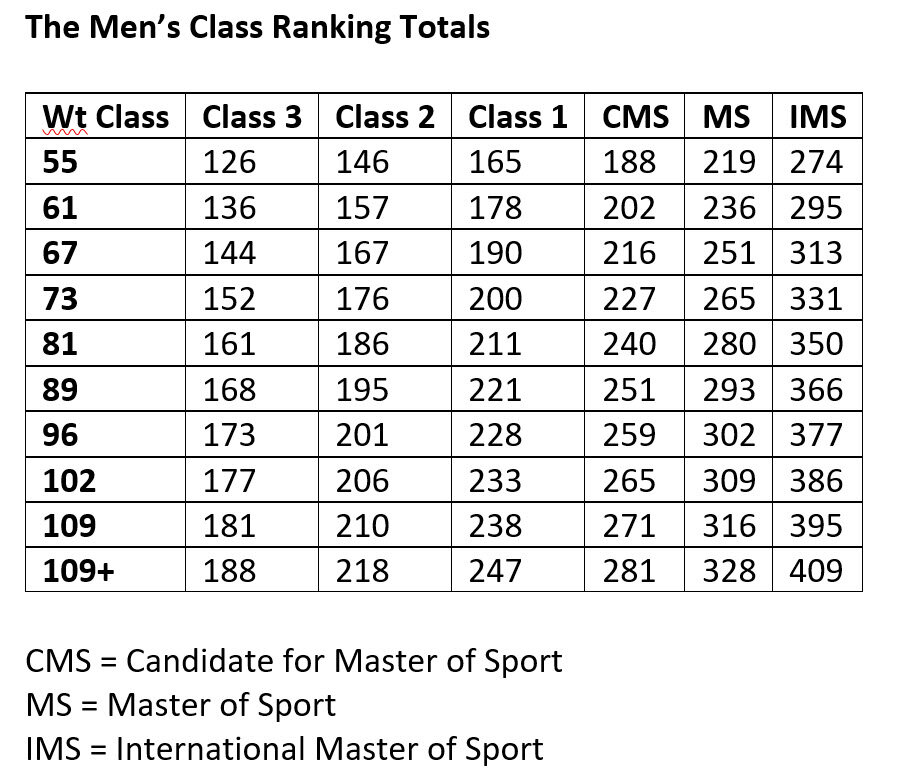

New Classification Numbers for Weightlifting Programming

Thank you!

Let me begin by thanking all those who’ve purchased my book, Weightlifting Programming. It was a project I’d wanted to complete for some time and I’m happy that so many found it useful.

The IWF Changes the Bodyweight Classes

Since the book’s publication in 2012, the IWF made the decision to change the bodyweight classes and introduced the new ones in 2018. These changes were done for two reasons. The first was to equalize the number of gold medals contested by men and women. The second was to retire records that were established under the less rigorous drug testing technology and politics of the past. Thus there are currently 10 bodyweight classes for men and 10 for women with 7 each being contested in the Olympic Games.

My Numbers

The introduction of new weight classes then made the numbers in Weightlifting Programming more inconvenient to apply although they can still be used. For my own purposes I decided to come up with some new classification totals to make that aspect easier to undertake. So whereas the first women’s class in the pre-2018 system was 48 kg and the total to achieve class 3 status was 80 kg, the new bodyweight classes begin with 45 kg and prior to this date I had not come across new classification totals.

Consequently I decided to calculate my own figures.

The Caveat

I calculated the figures in the tables at the end of this blog simply in order to make it possible to program more accurately. They are to be used in conjunction with the principles outlined in the Weightlifting Programming book. These are tools. I don’t want people calling them “Takano Numbers” because I’m not concerned with marketing them. I may use them to at some point to make up a ranking ladder of my own team members or even as qualifying totals for one of the local meets we conduct. Again, they are tools.

How I Calculated Them

For example for the women’s class 3 totals, I multiplied the Sinclair Coefficient for the limit bodyweight of each class times the Class 3 total for that bodyweight class. So for the 48 kclass, the Sinclair coefficient is 1.585087 and the Class 3 total is 80 kg. I multiplied the two and achieved the Sinclair Total which is 126.80696. I did this for each of the pre-2018 bodyweight classes, added them together and divided by 7 (the number of bodyweight classes) and achieved the mean figure of 126.76272. I then divided this figure by each of the coefficients for the upper limit of each 2018 bodyweight class, rounded them off to the nearest integer and achieved the results shown in the table.

A Brief Diversion on the Sinclair Numbers

The Sinclair coefficients are empirically derived and recalculated every quad. I am here using the 2017-2020 numbers. Thus I may have to recalculate these class numbers when the new Sinclair coefficients are released. The Sinclair coefficients are, as I understand, re-calculated by former students of the late Roy Sinclair who base them on the results of international competitions.

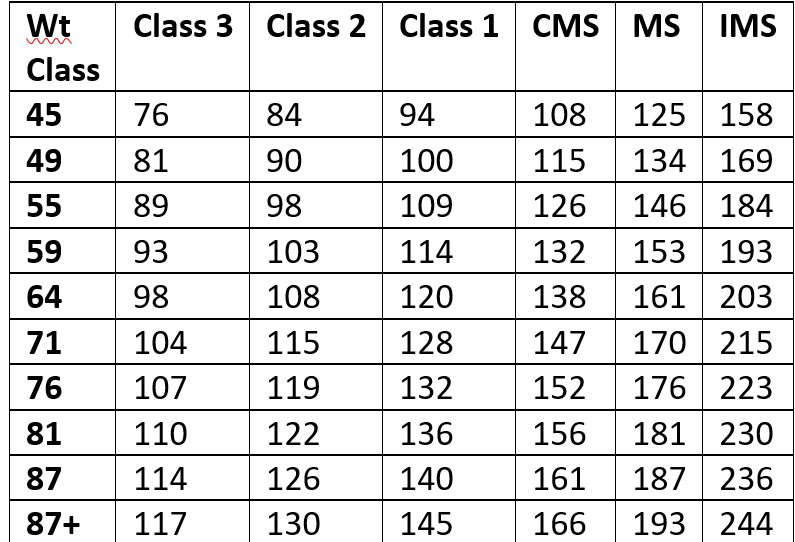

The Women’s Class Ranking Totals